My Four Hours In NY City,

A memoir by Colin Campbell

You can’t just walk into a Madison Avenue office building with a head in a two-cubic-foot box and expect to get right on the elevator. Somebody rushed up to me and ordered me to take the box to the service elevator in the back.

I was already pretty crabby. It was late winter and the New Yorkers were finely garbed in leather and fur coats that cost more than my car.

BBDO World Headquarters was untended when I arrived—everybody was out to lunch. I was able to take the box into the CEO’s office. I moved aside the papers on his desk and took the head from the box and placed it on the desk: a clay bust of Lee Iacocca impaled on the hubcap of a Chrysler Imperial. The bust had been jostled on the plane ride to New York and I moved Iacocca’s cigar back to its normal jaunty angle.

I cabbed back to the airport and waited in a bar. It was St. Patrick’s Day and the river was green. There wasn’t much else to do. I suppose I could have delayed my return ticket and stayed in New York and partied in some expensive bar somewhere, or gone to any of the famous places. But I hadn’t had a moment’s notice about the unexpected trip to New York. All I wanted to do was get back home. New York is a great place to live, but I wouldn’t want to visit there.

The day had started with a vicious hangover. The day before, new Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca had fired BBDO from the Dodge account. Nothing personal: he also fired three other ad agencies who had the Plymouth, Chrysler, and Jeep accounts.

I learned about it when I returned to the office after spending all day at my first-ever meeting with actual Chrysler Corporation executives.

I was the junior copywriter at BBDO Detroit and after a year and half on the job I was finally allowed to meet the client. I’d made a strong, forceful presentation about how the upcoming Dodge Caravan mini-van should be marketed, and the BBDO Dodge Truck Division manager complimented me about it as we rode back to the office. And when we arrived the halls were filled with weeping women. “We lost the account,” one of them told me.

“Sure,” I said. BBDO had had the account since 1944. If anything seemed permanent it was the Dodge account.

But it was true. A hundred million dollar account gone, bang zoom. And no other accounts at the Detroit office.

All of us from the Creative Department went to the Machus Red Fox bar on Woodward, the usual hangout for Detroit adbiz folks, the bar where Jimmy Hoffa was kidnapped from, and drank our brains out.

The next morning I was the last Creative who straggled into the office and so I won the booby prize of a six-hour trip to New York. And the day after I got back from New York we were all officially fired.

“Don’t expect anything from us,” the agency head said, smiling and waving as he left in his chauffeured Lincoln Continental Mark V. He ordered that the agency be shut down and the offices closed as fast as humanly possible. By the time we got back from the announcement meeting there were fresh padlocks on all the storeroom doors and workmen were tagging and carting away equipment.

I’d been there for one year, during which time I’d written more ads than anybody else at the agency. I’d left Santa Barbara after three years of working at SB Magazine, flat broke despite lots of freelance sidejobs

My brother in Detroit was working at the ad agency for Buick and he told me “It’s raining soup here,” so I borrowed money for plane fare and went to Detroit on a rainy Monday, spent Tuesday sleeping off the trip, Wednesday setting up interviews, and on Thursday my first interview was with the copy director at BBD&O and he loved my portfolio.

Somehow he had seen my ad for Gordon & Grant Redwood Hot Tubs--it was featured in COMMUNICATION ARTS magazine–and was impressed by it. Also, he had just read an article in ROAD & TRACK magazine about the Boa Aerocon car being manufactured in Santa Barbara–I designed and wrote a brochure for it. He just about did handsprings over the interior shot with the headlights glowing.

He asked me how much I was looking for and I tremulously asked for $18,000, which I thought was pushing the limit, and he director laughed and said, let’s make it $21,000.

At that time, $21,000 was the MLB minimum wage. I was making as much as the Detroit Tigers’ new shortstop. (The CPI Inflation Calculator tells me that $21,000 back then is equivalent to $108,000 today.)

He told me that he was glad I came along, that they had been looking for somebody for three or four weeks but had seen only inexperienced kids just out of school or tired old hacks.

It was gratifying. Later I found out that BBDO had recently hired some of the highest-priced creative talent in Detroit in an attempt to change the course of Chrysler’s advertising.

But things started to unravel as soon as I started. The first meeting I went to was about the new Dodge cars and trucks that would be introduced in the fall–six months away.

The meeting was a slide show, quite a costly presentation in terms of man-hours. The Chrysler executive talked about this year’s Aspen, and this year’s Omni, and then we broke for lunch at a nearby restaurant. The BBDO boss told us, “No booze at lunch,” but the creative department drank martini after martini and became disgustingly drunk, rude to the waitresses, and abusive of the Chrysler account man. When the meeting resumed, the Creatives jeered and catcalled and threw things as the account man hustled through the charts and graphs and gave up around 3pm.

I didn’t drink, I was the only sober one at the conference table. I hadn’t had a drink in four months. By the end of my time at BBDO I was drunk every day and was spending a hundred bucks a week on cocaine.

Such a change from when I started at BBDO until I left. I stopped drinking on my 31st birthday and four months later I landed a job at the fourth largest ad agency in the world.

If I’d known what was going on I would have had a premonition on my first day. The agency hired an art director to start the same day as me.

However, on the night before we were supposed to start, he went to the top of the 16-story office building and jumped off. I didn’t learn of this for several weeks after I started. I found out that suicide was a way of life in the Detroit adbiz creative community.

Amazing how many good campaigns were created at BBDO during my time there. Created-and then junked because of bureaucratic jitters.

The Chrysler fatcats could diddle with us up to a final date, and they took every advantage of that, a fat housecat playing with a tired and crippled mouse. The Corporation decided that the slogan for the car called Magnum would be “The Name Says It All,” so BBDO made a commercial that rode the concept all the way: a James Bondish descent down a big-city parking structure, with gritty sound and hands working shifters and aircraft-like dashboard and tough cornering, and not a word of narrative until the car reached the street and surged into the traffic. MAGNUM. THE NAME SAYS IT ALL.

Would it have been effective in selling the car? Hard to say. Jittery Chrysler admen yanked the whole Magnum campaign, and the 1979 Magnum models hit the showrooms with no advertising behind them.

The bureaucrats were able to make changes with impunity. Therefor, changes were made continuously, until some outside fact (like the date of the World Series telecasts) forced coagulation of whatever currently existed. Thus went on the air the commercials with dogs driving cars, Napoleon strutting around talking about the car that’s Big For It’s Size, a New Orleans funeral cortege marching past the last of the land whales, the Dodge St. Regis.

I went to a bar to watch the World Series on a giant-screen TV. I saw my ads running and saw that nobody in the bar was looking at the ads. Instead of being proud that my stuff was being aired in the Fall Classic, I was ashamed of what we’d done.

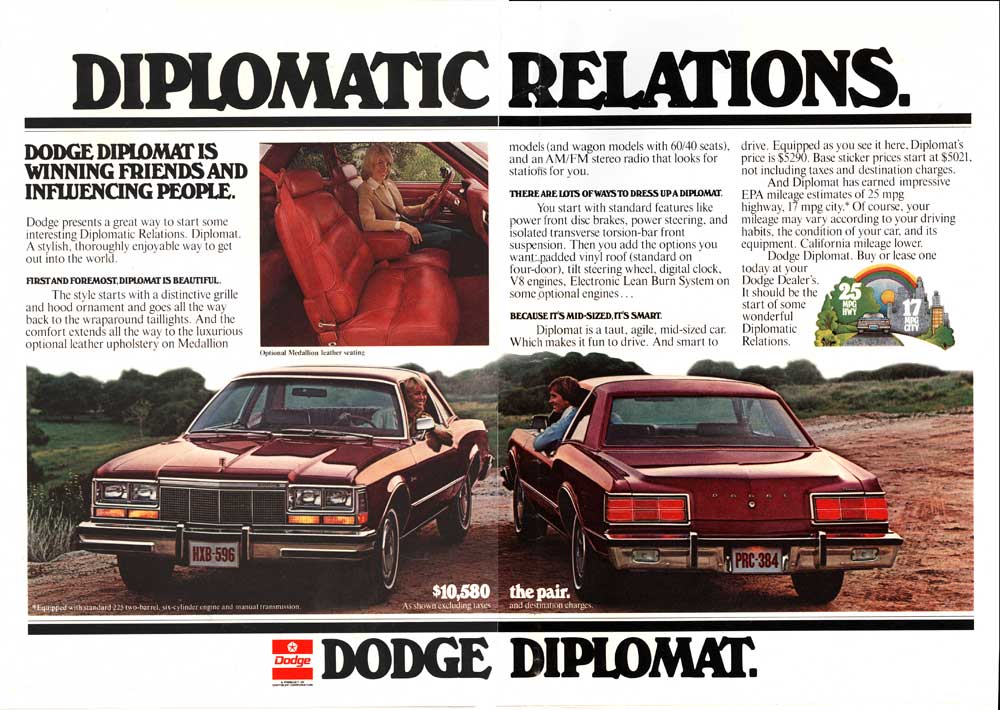

I wrote hundreds of radio, TV, and print ads for Dodge cars and trucks, but it felt as though I was merely inserting commas as the ads went by in the production line. My influence on the ads was minuscule and invisible. I won a Caddy Award from the Detroit Creative Directors Council for this two-page magazine ad for Dodge Diplomat:

I told them to give the award to the Chrysler account man’s wife who had the headline come to her in a dream and I was assigned to turn the headline into an ad. I have no idea why it was selected to receive an award.

After we were all fired, the ad agencies for the other car companies called and made attractive offers, but I was sick of the Detroit agency business. And then BBDO asked me to come back–they were contractually required to service the Dodge account for 90 days until the new ad agency got up to speed, so if any emergencies came up, I would take care of them.

So I moved into the Creative Director’s corner office with a view of the Detroit skyline 18 miles away and did nothing for three months. I found a sheaf of Detroit Tiger season tickets in the Creative Director’s desk and I went to just about every game.

On May 31, 1979, I left my job at BBDO and prepared to uproot myself from Detroit and move to Santa Barbara, California. I left it at 3:30 in the afternoon after watching my production crew film a Dodge Truck commercial at a high-rise construction site.

The commercial was supposed to show how tough Dodge trucks were and how economical, but the script had suffered eleven revisions after it left my hands and I felt detached from it. The voice-over was recorded two days before. The ad was finished except for this formality of filming it. They did it wrong: the actors were pallid fakes and handled the bricks and lumber and sacks of cement as if with tongs. The real construction workers hooted down from their high-iron work and catcalled and yelled insults. They were a brawny and jovial pack of swaggering Montrealers, most with Mohawk Indian blood and all with a humorous contempt for the groundhogs below.

All of us groundhogs knew we were just going through the motions, the last feeble reflexes of dying nervous system. Even this final spasm of activity carried the stamp of BBDO management. “Look, Colin, I don’t care if it makes sense or not, it’s what the client wants, and I am not going to make a big stink with him—we’re talking about the last $600,000 they’re going to spend.”

It didn’t matter what the ad looked like or said and we all knew it. All that mattered was that 30 seconds of air time be filled.

We filmed hours and sent the film into the processing system and that was that—none of us would have any say in what happened further. I shook hands with the BBDO people at the site, for this was our last meeting, and I drove twenty miles back to the Leaning Tower of Troy to pick up my final paycheck and severance pay.