A Memoir About My Father

by Colin Campbell

I started writing when I was 3. I remember the first thing I wrote.

My parents ignored the content of the writing and instead criticized my selection of materials: a black crayon on the living room wall. The text said, “llllllll.” A row of lower-case cursive L’s. It looked like writing to me.

When I was a kid I never knew why my mother was so antagonistic toward me. It wasn’t until a few years after they were both dead that I realized what the reason was that made my mother hate me so much: I’m a physical double of my father and I have the same gifts of art and wit that he had.

She was punishing Pop, not me. Pop was an artist of high accomplishment and it turned out that she preferred the company of criminals and drifters.

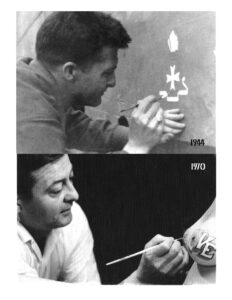

My father wrote whenever he was home. He had a drawing board with a square cut out of the middle and replaced with a plate of frosted glass with a couple fluorescent light bulbs underneath to make it easy to trace letters. He was a lettering man for an art studio. He drew words.

Today if you want a bigger headline you just select the text and hit a control and bump it up to whatever size you want. Back then, if you wanted type of a size different from the metal fonts in the font case, you had to draw it from scratch. Or have a new font made in that size. It was cheaper to hire some artist and have him draw the words.

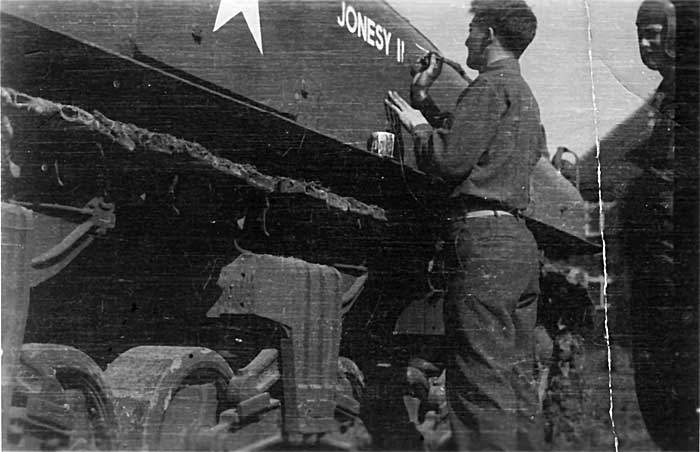

He was a World War 2 veteran, same as everybody else’s dad. He was with the 2nd Armored Division under Patton from North Africa, Sicily, Normandy, and the Battle of the Bulge. He was the guy who played harmonica in the foxholes. When they got to Normandy there were plenty of camera stores in cities along their battle route where he could acquire film and film developing supplies and he began processing film and making contact prints for himself and all the other guys who were taking photos. He also became the guy who was good at painting a name on your tank.

A few decades later, he was painting the tits of Playboy models.

A few decades later, he was painting the tits of Playboy models.

He came back from the war in a troopship and he was able to hear a Tigers radio broadcast while at sea–it was late summer of 1945 and Hank Greenberg’s homers had Detroit on the way to the World Series.

He’d been corresponding with my mother while he was at war; she graduated from high school in 1944. I was conceived around February 1946. I’ve never heard a word about my parents’ wedding or if they even had one. No photos exist.

According to one of his pals from the old days, Pop used the GI Bill’s 52/$20 Club ($20 a week for one year to help transition veterans to civilian life) to hang out in bars and get into fistfights. Then I was born and he found a job as an apprentice lettering man at a Detroit art studio, which was something he’d always wanted to do. Before the war he’d had a fledgling business painting lettering on store windows.

And then he prospered. He bought a house in a new subdivision.

My sibs Scott, Matt, and Lanie were born. Pop built a two-bedroom addition to the house just before Lanie was born. A year and a half later the twins Mary and Gerry were born and sometime shortly after that Pop vanished from the household. I was six and a half.

I was completely unaware of whatever event severed them from each other. Looking back, there was evidence but I was a little kid and I didn’t know what it meant. I remember being mystified when I was riding in the back seat while Pop was driving and his brother Uncle Curly was in the passenger seat and Pop was complaining about how Scott didn’t look like him, although Colin was a virtual duplicate, and Curly said, “What do you think you are, a goddam rubber stamp?”

All I knew was that Daddy wasn’t around anymore. He’d hardly ever been home, anyway. He played softball three nights a week in the summer and bowled three nights a week in the winter, and golfed every Sunday, weather permitting.

And he worked long irregular hours at his job because of the demands and pressures of the automotive advertising industry. So he was away from home a lot, and Ma fooled around on the side a lot.

In his old age Pop told me he’d slugged a neighbor he thought was doing it with Ma–back then, he was proud of breaking the guy’s tooth.

At some point he slugged Ma. Both families were shocked and Pop became a pariah. He entered into psychotherapy. He came out a changed man, he said. He became a different person. I guess I’ll never know what that previous person was like.

After he was gone there was just a constant blur of boyfriends who moved in for a year or so apiece. Ma liked ’em young. One time she had to give me a ride to junior high because I’d sprained my ankle in gym class and I could barely walk. Ma was afraid people at the school would see the two of us together, I guess. She told me that if anybody asked who was that in the car, I was to say she was my older sister. Not my mother.

On visitation day Pop took us to events and visits with his friends, who were also artists and creators. But most of the time he took us to his studio where he worked overtime to earn enough money for child support for the six of us. Plus Ma and her boyfriends.

My father was an athlete. He was the City of Detroit squash champion one year in the 1950s. Handball with a racket. I was thrilled to be the batboy for games with his fast-pitch softball team, where he was center fielder but mostly catcher, the most important position in the defense. One season his pitcher Ben threw five no-hitters.

He took us skiing. He was a very good skier.

He delivered the monthly child support check on the first of the month and never was late. The one time it was late was when the Friend of the Court decreed that all alimony and child support payments had to go to them first so they could make sure those rascals were actually making the payments, and the first Friend of the Court check was four days late. But that never happened again, startup woes, that’s all.

My father was the first president of the Graphic Artists Guild. I happened to be in town when he declared a strike against the ad agency for Chevrolet, and I carried a sign in the picket line in front of the agency’s office.

I grew up with a biker mama while my father zoomed to a successful career as a commercial artist, a glamorous life just outside of my grasp. Ma always wanted to present Pop in the worst possible light. Gradually as I grew up I began to realize that she was wrong on many topics, and she lied by reflex. Eventually it became clear I couldn’t trust her about a single thing.

I never understood why my mother was so opposed to my writing and drawing stuff, but now I realize it was probably because I was a mirror of my father doing the same kind of stuff.

I was semi-estranged from Pop for years because of the propaganda Ma pumped into me and my five sibs about what a terrible guy he was, after the divorce when I was 6. By the time I severed myself from my mother’s life I could see that her calumny was false, but he and I had a stiff, remote relationship.

I moved to California when I was 22 and saw him only sporadically until I went back to Detroit ten years later to take a job as a copywriter at the ad agency for Dodge cars and pickups.

The BBDO office was only three miles from Pop’s typography studio and I joined his weekly Tuesday lunch meetings with other freelance graphic artists of his generation. The Detroit adbiz was dominated by cars and we bitched about the industry rumors and sometimes we drank a lot.

One time I asked Pop to meet me for lunch on a different day, not with his gang of regulars, at a restaurant he used to take us to when we were little, a place where you ate at a counter with Lionel train tracks. You checked off your order on a menu, and then a while later a train came down the track with your food.

He was extremely wary when we met and it turned out that he thought I had some deep dark thing to discuss, but, no, all wanted was an hour with my father to talk about things other than the Detroit graphics industry.

So he relaxed and we talked about Campbell family history. I didn’t know anything about his parents because they were both dead before I was born. His mother died when he was 9 and the Great Depression began and his father was destitute and he placed my father and his three brothers at various foster homes. I found out that one of my brothers was named after Pop’s foster father.

We remained good pals for the rest of his life.